The Philistines were an ancient people who settled along the southern coast of Canaan during the Iron Age, establishing a confederation of city-states collectively known as Philistia. Their interactions with neighboring cultures, especially the Israelites, have been well-documented, yet their origins and cultural identity have long been subjects of scholarly debate.

Origins and Migration

Scholarly consensus suggests that the Philistines originated from a Greek immigrant group from the Aegean region. This group settled in Canaan around 1175 BC, during the Late Bronze Age collapse. Over time, they intermixed with the indigenous Canaanite societies, assimilating elements from them while preserving their own unique culture.

Egyptian records, particularly inscriptions from the reign of Ramesses III, refer to a group called the “Peleset,” which is widely accepted as synonymous with the Philistines. These records describe the Peleset as part of the Sea Peoples, maritime raiders who attempted to invade Egypt and other regions during the late 13th and early 12th centuries BC. Following their defeat by the Egyptians, it’s believed that the Peleset settled along the coast of Canaan, establishing the Philistine cities.

Philistine City-States

The Philistines established a confederation of five primary city-states: Gaza, Ashkelon, Ashdod, Ekron, and Gath. Each city operated with a degree of autonomy but shared cultural and political ties. Archaeological excavations in these areas have revealed evidence of advanced urban planning, including industrial zones and sophisticated infrastructure. For instance, the city of Ekron was a significant center for olive oil production, with over 200 olive oil installations discovered, indicating a large-scale industry that may have produced more than 1,000 tons of olive oil, accounting for approximately 30% of Israel’s present-day production.

Cultural Practices and Material Culture

The material culture of the Philistines exhibits a blend of Aegean and local Canaanite influences. Pottery styles, architectural designs, and burial practices reflect this hybridization. For example, Philistine pottery, known for its distinctive bichrome decoration, shows similarities to Mycenaean ceramics, suggesting an Aegean origin. Over time, these styles evolved, incorporating local Canaanite elements, which indicates a process of cultural assimilation.

Burial practices further illustrate this cultural amalgamation. Excavations at a Philistine cemetery in Ashkelon revealed over 150 burials dating from the 11th to 8th centuries BC. The majority of the deceased were interred in oval-shaped graves, a practice common in Aegean cultures but not indigenous to Canaan. Some individuals were buried in ashlar chamber tombs, and a few were cremated, further indicating diverse burial customs. These findings suggest that while the Philistines maintained certain Aegean traditions, they also adopted local customs over time.

Language and Religion

The linguistic heritage of the Philistines remains a topic of debate among scholars. While the Bible does not mention any language barriers between the Israelites and the Philistines, suggesting some level of mutual intelligibility, other evidence points to a non-Semitic origin for the Philistine language. Pottery fragments bearing inscriptions in non-Semitic scripts, including Cypro-Minoan, have been discovered, indicating a possible Aegean linguistic connection. However, over time, the Philistines likely adopted the local Semitic languages, as evidenced by personal names and inscriptions from later periods.

Religiously, the Philistines practiced a polytheistic faith with deities that may have had parallels in both Aegean and Near Eastern pantheons. The god Dagon is frequently mentioned in biblical texts as a principal deity of the Philistines. Temples dedicated to Dagon have been excavated in Philistine cities, featuring architectural elements distinct from those of neighboring cultures. Additionally, artifacts such as figurines and cult stands suggest the worship of other deities, possibly including Astarte and Baal, indicating a syncretic religious system that incorporated both imported and local elements.

Economy and Trade

The Philistine economy was diverse and robust, encompassing agriculture, industry, and trade. In addition to their renowned olive oil production, the Philistines were skilled in metallurgy, producing complex wares of gold, bronze, and iron. Artifacts such as weapons, jewelry, and tools attest to their advanced metalworking techniques. The presence of breweries, wineries, and retail shops marketing beer and wine indicates a thriving industry in fermented beverages. Beer mugs and wine kraters are among the most common pottery finds in Philistine archaeological sites, suggesting that these beverages played a significant role in their daily life and trade.

The strategic coastal locations of the Philistine city-states facilitated maritime trade, allowing them to establish commercial networks with other cultures across the Mediterranean. Imported goods such as pottery, luxury items, and raw materials have been found in Philistine contexts, indicating active participation in regional and long-distance trade. This exchange not only bolstered their economy but also facilitated cultural interactions, contributing to the hybrid nature of Philistine material culture.

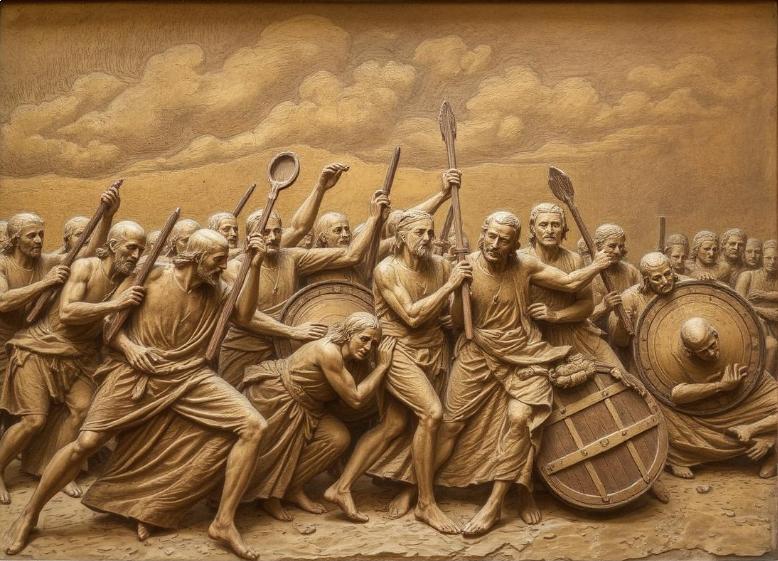

Conflict and Decline

The Philistines are perhaps best known for their conflicts with the Israelites, as detailed in biblical narratives. These accounts describe a series of battles and skirmishes, with the Philistines often portrayed as formidable adversaries. Notable figures such as Goliath, the giant warrior defeated by David, and Delilah, who betrayed Samson, are central to these stories. While the historicity of these accounts is debated, archaeological evidence supports the existence of conflicts between the Philistines and neighboring groups.

By the 7th century BC, the Philistines had come under the dominion of successive empires, including the Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian empires. In 604 BC, the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II launched a military campaign against the Levant, during which the Philistine city-states suffered significant destruction. The city of Ashkelon, for instance, was sacked and largely abandoned. This marked the beginning of the decline of Philistine culture as an independent entity.

The final blow to the Philistines came with the rise of the Persian Empire in the 6th century BC. The Persians reorganized the region, incorporating Philistia into the province of “Eber-Nari.” Over time, the distinct Philistine identity faded as they assimilated into the larger cultural milieu of the region, particularly under Persian, Greek, and later Roman rule. By the Hellenistic period, the Philistines had effectively disappeared as a distinct ethnic group, though their legacy persisted in the historical and biblical record.

Legacy and Modern Perspectives

The Philistines left an enduring legacy in both archaeology and cultural memory. Their interactions with the Israelites, as described in the Hebrew Bible, have profoundly shaped their image in popular culture. Terms like “Philistine” have even entered modern language, often used metaphorically to describe someone perceived as uncultured or indifferent to art and learning.

However, modern archaeology has painted a more nuanced picture of the Philistines. Far from being crude or uncivilized, they were a sophisticated and resourceful people who contributed significantly to the cultural and economic landscape of the ancient Near East. Their ability to integrate elements from various cultures while maintaining a unique identity speaks to their adaptability and resilience.

Closing Thoughts

The story of the Philistines is one of migration, adaptation, and eventual assimilation. As a people who bridged the Aegean and Near Eastern worlds, they serve as a fascinating example of cultural hybridity in the ancient world. Though their cities may lie in ruins, the Philistines’ influence continues to captivate historians, archaeologists, and the broader public, shedding light on a critical period of transition in the ancient Mediterranean.

Ancient Celebrities: Icons of Their Time

In today’s world, celebrities dominate our lives, from the silver screen to social media. But fame i…

The Legacy of Richard the Lionheart: England’s Warrior King

History remembers Richard I of England, better known as Richard the Lionheart, as a king of courage,…

Surviving Winter in Medieval Castles: How They Endured the Cold

The harsh winters of the Middle Ages tested the resilience and ingenuity of people far more than mod…